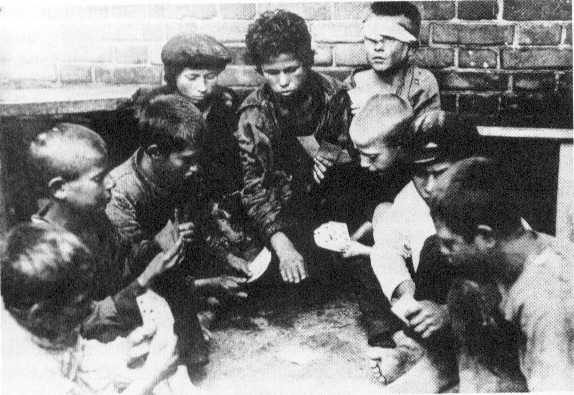

Among the 7 million orphaned children on the streets during the Russian Civil War

In this the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, you can now read about how the Bolsheviks prepared the way for Stalin in Dissent and Jacobin, the flagship publications of rightwing and leftwing social democracy respectively. Eerily enough, they sound like they could have been written by Karl Kautsky if he were alive today.

In Dissent, you can read Mitchell Cohen’s “What Lenin’s Critics Got Right” that is mostly a defense of Julius Martov, the Menshevik leader. Its curdled prose is steeped in historical minutiae that could be of less interest to young radicals trying to figure out a strategy for overthrowing the capitalist system. Besides trying to bury the October Revolution for the millionth time since 1917, Cohen makes a laughable attempt at debunking Marx whose critique of “social democracy” in the 18th Brumaire supposedly gave far too much authority to the working class as a universalizing revolutionary agency.

Reading this, I scratched my head and wondered what the hell he was talking about since the Second International was formed a full 37 years after the 18th Brumaire was written. What “social democracy” was Marx referring to? That was news to me.

It turns out he was referring to a party best known as the Mountain (Montagne) that had both small proprietors and working class members just like the Democratic Party in the USA but hardly resembling the party led by Karl Kautsky. It was instead a party led by Alexandre Ledru-Rollin that backed Louis Bonaparte’s 1851 coup. So much for “democracy”. As for the “socialism” part, the Mountain opposed the June Days uprising in 1848 that was triggered by the Second Republic’s decision to shut down the National Workshops, a measure enacted to create jobs for the unemployed. The National Guard was called out to suppress the uprising, leaving 10,000 dead workers in its wake and another 4,000 deported to Algeria. Why am I not surprised that Mitchell Cohen defends the Mountain against Karl Marx who had these pithy words for the counter-revolutionary party: “a nightmare on the brains of the living”?

In 2003, Cohen wrote that “Unless there is a coup, force will eventually be needed to defang Saddam’s regime. The only real questions are when, how much force, and what aftermath.” So that’s Dissent Magazine’s co-editor for you.

We turn now to Sunkara’s 7,500 word article on the Russian Revolution titled “The Few Who Won” that strikes a literary pose at the outset, referring to Cheka chief Felix Dzerzhinsky as if he stepped out of a Len Deighton novel: “By age forty, he was clad in black leather, designing a bloody terror as head of the young Soviet Union’s secret police.” Funny about that black leather thing. There are lots of pictures of Dzerzhinsky on the net but none in black leather. I guess the idea was to get the reader prepped to read something along the lines of “Darkness at Noon”.

The first 5,500 words or so are relatively favorable to Lenin’s party, even going so far as to describe the Russians as “freed from generations of oppression” in 1917. But in the last 2,000 words, Sunkara adopts the pose of prosecuting attorney, starting with the section titled “Terrorism and Communism” that evokes Karl Kautsky’s attack on the Soviet state in a 1919 book with exactly the same title. Was Sunkara consciously trying to recycle Kautsky’s polemics? I am afraid so.

All you really need to know from Kautsky’s book is this:

Those who defend Bolshevism do so by pointing out that their opponents, the White Guards of the Finns, the Baltic barons, the counter-revolutionary Tsarist generals and admirals have not done any better. But is it a justification of theft to show that others steal?

The lack of a class perspective here is shocking only if you are not familiar with the steep decline of the German socialist leader as the 20th century trudged forward. This is how Karl Kautsky described the social democratic government that had Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht’s blood on its hands in a 1934 book titled “Hitlerism and Social Democracy”. Congratulating his party for not sinking to the level of the Bolsheviks, he viewed its peaceful, parliamentary behavior as beyond reproach even if Hitler used it to his advantage:

Attempts to bring about the establishment of an anti-Bolshevist reign of terror under a Social Democratic regime were not lacking, as was evidenced by the assassination of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, an assassination perpetrated by a group of reactionary army officers. But the Social Democrats must consider it fortunate that the Social Democratic government of that time repelled with horror every effort of the frenzied army officers to force it to adopt terroristic measures.

Sunkara compares Lincoln’s draconian measures during the Civil War to those imposed by Lenin in 1918. Unlike Lenin, Lincoln’s suspension of civil liberties was a temporary measure but in the USSR they persisted under Stalin. This comparison is specious. To make a real comparison, imagine if both Mexico and Canada were slave states that intervened on behalf of the South. Additionally, what if England and France were also slave states that had joined in? A pincer movement of all four states seizes large parts of the North, sweeping up freed Blacks and returning them to the South. It also strikes deadly blows at the infant industrial capitalism of the North based on free wage labor. All the textile factories of the New England states are burned to the ground and their workers lined up and killed by counter-revolutionary firing squads.

After four years of bloody civil war, the North finally drives out the invaders and—licking its wounds—tries to return to normal. But not being satisfied with their defeat by the largely working-class Union army, the four invading slave states begin amassing armies on the North’s borders and issuing threats once again about the need to overthrow the Radical Republicans. Under these conditions, the NY Times, the NY Herald and other newspapers begin to echo slave state propaganda while the pro-slavery Democratic Party inside the North begins to organize mass demonstrations calling for reunification with the South but under its socio-economic umbrella. How long would the Radical Republicans put up with this? You can bet that Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman would have been even a much bigger bad-ass than Felix Dzerzhinsky.

Of course, some would argue that this is the kind of excuse Stalin used when he cracked down on dissent, jailed protesters, ruled by fiat, etc. That is best answered using the tools of historical materialism. When the social democrats argue that there is no difference between Red Terror and Stalin’s Gulags, they inevitably paper over crucial class distinctions. In the Russian civil war, the terror was directed against those who wanted to restore the status quo ante while in the 1930s the Gulags were filled with ordinary working people and peasants fed up with bureaucratic privilege and repression. The class differences were crucial.

Sunkara reviews Bolshevik policy during War Communism and finds it lacking. The peasants were forced to supply grain to the cities at gunpoint, thus turning them against the government. To satisfy the peasants, it would have required a return to market relations in the countryside as occurred under the NEP but in 1918 those same market relations would have caused mass starvation in the cities. The logical conclusion but one only hinted at by Sunkara is that Kautsky was right. A country that was so steeped in backward agrarian relations had no business trying to bypass capitalism. That, in fact, was also what Lenin believed until 1917 when four years of war and austerity drove the masses to such a boiling point that they cast aside all the “moderate socialists” and, taking the July Days into account, the Bolsheviks as well if they could not relieve their suffering. Sometimes, history had a dynamic that is impossible to overcome. One should not blame the Bolsheviks for making the peasants angry. You really need to put the blame on the industrialists and financiers that launched WWI, with the full support of social democratic parliamentarians.

Those looking for a full-bodied assessment of civil war economic realities will have to go somewhere else besides Sunkara’s article that was only capable of this bland observation: “The Soviet state’s political base was decimated, too. Some industrial workers died in the Civil War, while others left starving cities and tried their chances in the countryside.” That’s 28 words to cover one of the greatest disasters of the 20th century.

To really get a feel for the destruction wrought by counter-revolution in the USSR, you have to turn to John Rees’s 1991 article “In Defense of October” that was mostly a polemic against Samuel Farber. (Unfortunately, Rees was incapable of applying the same dialectical analysis to Cuba back then or to Syria today.)

So what were the conditions facing the Bolsheviks? The civil war broke over a country already decimated by the First World War. By 1918 Russia was producing just 12 percent of the steel it had produced in 1913. More or less the same story emerged from every industry: iron ore had slumped to 12.3 percent of its 1913 figure; tobacco to 19 percent; sugar to 24 percent; coal to 42 percent; linen to 75 percent. The country was producing just one fortieth of the railway track it had manufactured in 1913. And by January 1918 some 48 percent of the locomotives in the country were out of action. Factories closed, leaving Petrograd with just a third of its former workforce by autumn 1918. Hyperinflation raged at levels only later matched in the Weimar Republic. The amount of workers’ income that came from sources other than wages rose from 3.5 percent in 1913 to 38 percent in 1918 – in many cases desperation drove workers to simple theft. The workers’ state was as destitute as the workers: the state budget for 1918 showed income at less than half of expenditure.

Starvation came hard on the heels of economic devastation. In the spring of 1918 the food ration in Moscow and Petrograd sank to just 10 percent of that needed to sustain a manual worker. Now it was Chicherin, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, who ironically repeated the threat first made by the millionaire Ryabushynski: ‘The bony hand of hunger may throttle the Russian Revolution’. Disease necessarily walked hand in hand with starvation, claiming perhaps 7 million lives during the civil war, the same number of deaths as that suffered by Russians in the First World War. The tone of this cry from Lenin testifies to the seriousness of the crisis in 1918:

For God’s sake, use the most energetic and revolutionary measures to send grain, grain and more grain!!! Otherwise, Piter [Petrograd] may perish.

I urge you to read Rees’s entire article as well as one written by his comrade Megan Trudell titled “The Russian civil war: a Marxist analysis”. She explains why the Red Army eventually prevailed even though its requisitioning of grain drove many peasants into the counter-revolutionary army:

The White regimes returned the land to the landowners and the factories to the owners, denied trade union rights to workers, and were characterised by corruption, decadence, speculation and bitter repression of the population. The class in whose name the Whites fought was weak and crumbling, and was savagely lashing out in its decay. Within industrial centres controlled by Whites a reign of terror against workers was routine. In the Donbass, one in ten workers were shot if coal production fell, and ‘some workers were shot for simply being workers under the slogan, ‘Death to callused hands’.

Characterised by one of Kolchak’s generals as, ‘In the army, decay; in the staff, ignorance and incompetence; in the government, moral rot, disagreement and intrigues of ambitious egotists; in the country, uprising and anarchy; in public life, panic, selfishness, bribes and all sorts of scoundrelism’, the White regime at Omsk was a brutal and arbitrary dictatorship. It liquidated the trade unions and meted out savage reprisals against peasants who sheltered partisans–reprisals which inflamed the population and pushed many towards Bolshevism. When Omsk was taken by the Red Army in November 1919, it was with the willing participation of large numbers of peasant recruits. In many Siberian towns workers overthrew the Kolchak government before the Red troops arrived. In Irkutsk a Political Centre was established to govern in place of the Whites, which in turn was replaced by a mainly Bolshevik revolutionary committee installed by the workers in January 1920, to whom Kolchak was delivered after his capture.

Let me conclude with some comments on the final words of Sunkara’s article:

For a century, socialists have looked back at the October Revolution — sometimes with rose-colored glasses, sometimes to play at simplistic counterfactuals. But sometimes for good reason. Exploitation and inequality are still alive and well amid plenty. Even knowing how their story ended, we can learn from those who dared to fight for something better.

Yet both the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks were wrong in 1917. The Mensheviks’ faith in Russian liberals was misplaced, as were the Bolsheviks’ hopes for world revolution and an easy leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom. The Bolsheviks, having seen over ten million killed in a capitalist war, and living in an era of upheaval, can be forgiven. We can also forgive them because they were first.

What is less forgivable is that a model built from errors and excesses, forged in the worst of conditions, came to dominate a left living in an unrecognizable world.

Does the word model really apply to the USSR? Unless you were in a Maoist sect or the CP, the word model was the last one you’d choose to describe your outlook on the former Soviet Union. Except for the arts in the 1920s, there was not much to admire if you thought of the USSR as a kind of balance sheet with credits on one side and debits on the other. For my generation, Vietnam, Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela were much more in keeping with socialist ideals but they too were vulnerable to the same kinds of pressures that were put on the Bolsheviks. Despite the best intentions of the revolutionaries, the need to function in a largely capitalist world, even more so in the aftermath of the end of the USSR, forced the state to make painful adjustments.

Were any of these countries modeled on the Soviet Union? Except for the occasional display of the hammer-and-sickle, there’s not much evidence of that. Cuba, in particular, owed a lot more to José Marti than to V.I. Lenin. For the American left, the need is to build a movement that draws from native grounds, in the words of Alfred Kazin. Just like the Cubans referred back to José Marti and the Nicaraguans to Augusto Sandino, we need to connect with our own revolutionary traditions. That is why a group of us are involved with the North Star, a website that is named after Frederick Douglass’s newspaper.

Perhaps the main lesson to be drawn from the Bolsheviks is not about statecraft but how to struggle. Lenin’s main contribution, building upon those of Marx and Engels, is to draw class distinctions. If there’s anything to be gleaned from his writings, it is the need to make sharp class distinctions with the capitalist parties. In his day, this meant the Constitutional Democrats (Cadets) while today it means opposing the Democratic Party.

As was the urgent task in Lenin’s day and just as much today, it is to build a revolutionary party. Unfortunately, the conditions that made it possible to jump-start such a party in the early 1900s no longer exist. Largely through the guidance of Frederick Engels, it was possible to build a Second International that provided a kind of template for party-building, including the Russian social democracy. Once that movement collapsed as a result of its support for WWI, the Comintern stepped into the breach. It was a movement much too reliant on the Kremlin, even before Stalin’s rise to power. In the same way that the Second International turned into an obstacle for world revolution, so did the Third International.

Today, the revolutionary left is in a very weak position but freed from the constraints of the epoch of Second and Third International domination when, for example, the reformist politicians in France could derail the May-June Events of 1968. We are living in a period when neither the Stalinist parties nor the social democrats have mass followings. However, the same economic tendencies that caused their decline are also eroding the social base of the revolutionary movement. With traditional blue-collar jobs disappearing, the trade unions no longer have the kind of weight they once had.

To figure out where to go next in a world that is “unrecognizable” in terms of October 1917, as Sunkara put it, we need to engage with the new social terrain using the same kind of analytical tools Lenin brought to bear when he wrote about the growth of capitalist property relations in the Russian countryside. What are the social forces gathering momentum that can begin to cohere as a conscious opponent of a capitalist class in decline?

Despite my criticisms of Jacobin, it does provide much-needed political analysis about the changes taking place in the USA today. My hope is that it will begin to abandon the orientation to the Sanders wing of the Democratic Party that offers false hopes. The best thing it can do is provide some leadership to the DSA that has the potential of serving as a linchpin for a new radical movement that can set the bourgeoisie back on its heels. With 25,000 members, it has the capability of providing the leadership that was on display in the early days of the Trump administration when bodies were put on the line to oppose his immigration bans. This means transforming the DSA into something much more like a serious and disciplined organization that knows how to kick ass and take names. If it instead prioritizes ringing doorbells for the Democratic Party, something else will have to take its place.

I think you’re really misreading Sunkara. By “model” I’m sure he means the bureaucratic centralist party.

I wrote a response to Cohen’s awful piece which I hope will be printed in a future issue of Dissent.

Comment by jschulman — December 20, 2017 @ 8:00 pm

Good critique. Re your statement: “Funny about that black leather thing. There are lots of pictures of Dzerzhinsky on the net but none in black leather,” if Dzerzhinsky wore leather, he may well have been inspired by Sverdlov, if Trotsky is to be believed: “In the initial post-October period the Communists were, as is well-known, called ‘leatherites’ by our enemies, because of the way in which we dressed. I believe that Sverdlov’s example played a major role in introducing the leather ‘uniform’ among us. At all events he invariably walked around encased in leather from head to toe, from his leather cap to his leather boots. This costume, which somehow corresponded with the character of those days, radiated far and wide from him, as the central organizational figure” (Trotsky, “Portraits: Personal and Political”). Lenin said about Sverdlov: “In the course of our revolution, in its victories, it fell to Sverdlov to express more fully and more wholly than anybody else the very essence of the proletarian revolution.”

Comment by David Thorstad — December 20, 2017 @ 8:03 pm

As far as I know, Ledru-Rollin never backed the 1851 coup. I believe he was driven into exile in London where he was a leader in one of the many committees organized by members of the 1848 uprisings. Marx denounces him in Heroes of the Exile for many supposed flaws (including his closeness with Mazzini) but not for being an open supporter of Napoleon III’s coup. If he were, he would have been living in Paris in style and not London in exile.

Comment by Hylozoic Hedgehog — December 20, 2017 @ 8:17 pm

Well, the reference to the 1851 coup comes from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Mountain_(1849).

“Combs has pointed out that the demands of voters were expressed in a number of different ways and that support was fleeting (wine growers were also prepared to back Louis-Napoléon or the Bourbons to get excise duties cut), and that peasants in the south-west and Massif Central who backed The Mountain also accepted Louis-Napoléon after his coup of 1851, and the end of the Second Republic. For the remainder of the Second Empire, Louis-Napoléon found the core of his support lay in the peasantry.”

This doesn’t sound right to you?

Comment by louisproyect — December 20, 2017 @ 8:39 pm

excellent analysis. Drawing the class line is out main task today in my opinion, as necessary for the creation of a mass working class based political Party.

Comment by Les Evenchick — December 21, 2017 @ 2:02 am

our not out

Comment by Les Evenchick — December 21, 2017 @ 2:03 am

Not really. As for L-R, there is no doubt he was a bitter opponent of the coup. He fought it in exile as an 1848er. As for the Mountain, when Napoleon III took power, he more or less suppressed any political resistance so it would not surprise me if some peasants in the Mountain eventually wound up supporting him. So did the working class, actually, as did the bourgeoisie. Napoleon III famously legitimized the coup with a referendum where the voters overwhelmingly backed his coup. And they came from all walks of life although the peasantry was the largest vote because there were more peasants in France than any other group to begin with. But I think it’s entirely misleading to portray Napoleon III as an expression of rural ideology. After all, he was a remarkable modernizer of French life, as Paris demonstrates for good and ill.

Marx — no fan of the countryside — claimed that Napoleon III’s rule was based on the peasant “idiocy of rural life” and in the 18th Brumaire, he predicted a quick toppling of Napoleon III. Instead, Napoleon III consolidated his rule and he dominated Continental Europe for decades. He was something like a Peron figure in that the played to the left (in part via “Plon Plon” whom Marx also despised) and the Catholic right and ruled France with surprisingly little opposition. This is why the London exiles felt themselves in such a difficult position.

Napoleon III only fell because he stupidly declared war on Prussia, not because of any working class threat in France. So the idea that former members of the Mountain may have backed him may well be true but so did many many others, including the high bourgeoisie.

I’ve always found Marx’s wildly optimistic analysis of Napoleon III in 18th Brumaire contrary to the obvious facts of mid-19th century French history even though his sociological analysis of the concept of “Bonapartism” remains brilliant. Then again, Marx was one of those London exiles himself and he maintained hope for a time that there would be a new wave or revolt. But he simply misread Napoleon III’s staying power. In fact, Napoleon III’s staying power led him to a better understanding of the staying power of the state as such.

In any case, L-R most certainly did not support Napoleon III.

Comment by Hylozoic Hedgehog — December 21, 2017 @ 5:05 am

Those poor misunderstood Mensheviks who wanted to continue the slaughter of World War 1.

Comment by Bill — December 21, 2017 @ 8:11 am

[…] What can we learn from the Russian Revolution? A reply to Jacobin […]

Pingback by “What can we learn from the Russian Revolution? A reply to Jacobin” | Louis Proyect: the Unrepentant Marxist | COMRADE BOYCIE: VIVA THE ANTI-TORY/BIG BROTHER REVOLUTION! — December 21, 2017 @ 11:44 am

Comment by Farans Kalosar — December 21, 2017 @ 11:53 am

If there was no “working-class threat” in France during the first three quarters of the nineteenth century, where did the Commune de Paris come from in 1871?

Surely the mere fact of Nap. III ‘s defeat and chute can’t account for all of it. Are we to assume that the revolutionary wave of 1848 just died in its tracks after 1852?

Indeed why the somewhat staged back-and-forth between Prince Louis “Plon Plon” Napoleon (aka “ craint plomb [fears lead] because of his absence from the Battle of Solferino) and the “liberal” faction in the empire as vs. the Empress Eugenie and the Catholic right? If “no

threat,” why the countermeasures?

I wouldn’t care to match historical wits with Hylozoic on a dare–am in fact in history class to him and Louis here and struggling to stay afloat–but while it may be true strictly speaking that the working class did not overthrow N III, surely it would be myopic to say, especially in the light of ensuing events, that there was no working-class threat.

The fellow didn’t survive and thrive as long as he did merely by farting the Marseillaise through a French horn.

Marx, 18th Brumaire, describes NIII’s performance thus:

This juggling act may have been kept going for an astonishingly long time, but that does not make it any the less a juggling act.

The history of capitalism’s survival currently is one of clown juggling acts sustained in power by insuperable national divisions between the workers of the world and the insidious power of bourgeois ideology. The latter somehow gets straight into people’s unconscious minds, borne in part on the insidious, psyche-penetrating vector of religion, with which it is nevertheless crucially not precisely identical–even in the minds of the skeptical and liberally irreligious pseudo-intelligentia.

We are seeing this in the US today. Final victory may not be inevitable, but the threat of revolution exists and is being fought strenuously–above all by the Democratic and Republican political fartfests, sustained by universal mental slavery.

Comment by Farans Kalosar — December 23, 2017 @ 2:03 pm

The “working class threat” didn’t die but it went on life-support because Napoleon III had great backing in France among all the classes. He was a very successful ruler. This is why his 1851 coup didn’t trigger a huge revolt as Marx and the other exiles thought. Instead it led to a referendum where he was overwhelmingly backed as the classical man on horseback who returned France to stability after years of political chaos. (Think Putin.)

What Marx wrote (and you quote) strikes me as blather, quite frankly. Later on, Marx learned to take Napoleon III more seriously. That said, Napoleon III did play coalition politics and this helped him maintain his rule. He would pander to the Catholic Church on the one hand and the more enlightened bourgeoisie on the other. He made sure to be sympathetic to the working class to some degree but not so sympathetic to totally alienate the business class.

Bismarck looked to Napoleon III as a model ruler and Bismarck went out of his way to court the artisans as well. He even tried a back-deal with Lassalle against the “Manchester School” German liberal party. Again, it was because in part Bismarck saw Napoleon III as a model ruler for a modern age. Because Napoleon III was a sophisticated ruler, some exiled radicals began turning to assassination plots once they lost hope in any return to an 1848-style uprising. In any case, as you point out, he did play to the Catholics on the one hand and on the other to the “liberal” faction and managed to balance them off. In short, the classic definition of “Bonapartist rule.”

In Herr Vogt, where Marx does take Napoleon III more seriously (although in his Russophobia, Marx thought Napoleon III somehow a pawn of the Tsar), he makes the point that not only was Napoleon III playing to “the liberals” but he was playing to the “1848ers” such as Carl Vogt, the former head of the the German left-liberals in Frankfurt then living in exile in Switzerland. Napoleon III said to them that since Austria was the arch-reactionary power in Italy and also a drain on progressive German unification, they should bloc with France/Piedmont-Savoy in the 1859 war. Napoleon III courted Kossuth and the anti-Hapsburg Hungarians as well. In short, he was not the simple-minded idiot backed by stupid peasants that Marx first made him out to be.

Again, in context, Marx and the other exiles in the period 1849-51 couldn’t be sure that a next 1848 wasn’t just around the corner even though Marx and Engels were much more skeptical than the rest. But the fact remains that there was no major working class uprising in France until arguably the CP-led strikes that contributed to the formation of the Blum government and later in 1968 (at least for a couple of weeks). Although France did develop a large Socialist Party in the late 1800s under the Third Republic, the decision of Millerand to enter the French Cabinet launched a huge crisis in the SP that was never really resolved just as “Bernsteinism” was never resolved. And the post-Jaures French left backed the government in World War I as we know.

So the “working class threat” was indeed muted. The greatest threat to the Third Republic probably came from the right, which came close to overthrowing the government in the early 1930s when the right almost stormed the parliament building.

As for the period we are discussing, there was no “working class” in France in the sense commonly meant. It was overwhelmingly artisan. The most popular expression of artisan radicalism in the 1850s was Proudhonism, which was very consciously anti-political. Or it was Blanquist. The Blanquists had nothing to do with the working class per se as they were a group of intransigent conspirators who launched one failed coup d’etat after another.

The French working class in any modern sense began to take shape much later. The French delegates to the First International were from Napoleon III sanctioned associations. Even they were pretty small potatoes as they were highly skilled and not workers in mass factories because these factories still didn’t exist in any significant way. Actually the center of the working class in the late 19th century was in Belgium where mass industrialization came first to the Continent and also in the Ruhr. But Belgium was much more militant than the Ruhr, which tended to be dominated by Catholic trade unions if I recall correctly.

As for the Commune, it wasn’t just the “working class” but a much larger popular Republican movement that thought France should continue the fight against the Germans under a Republican banner given Napoleon III’s collapse. Before that, they completely supported the war. The Grand Orient Freemasons famously marched in Paris in support of the Commune. They were not working class. They were secular Republicans who wanted to see a secular Republican France, which finally came into existence with the Third Republic in the early 1880s.

The idea that the First International had anything significant to do with the Commune was a myth created by the anti-socialist press in part to demonize Marx. Marx thought the Commune was a tactical mistake and the First International played a minor role in the events in Paris. Marx contributed to his popular demonization with his defense of the Commune. But that was written after the uprising had been crushed. His essay on the Commune gave the popular press the excuse to claim he masterminded it when he certainly did not. He wrote his essay because he was so horrified at the mass slaughter of Communards that he wanted to protest on the record. But during the Commune, he thought it was a mistake although he told the Commune that they should seize the Bank of France and hold it hostage, something they failed to do BTW. Marx also paid a price for his essay as a whole wing of the British supporters of the First International broke with Marx as they viewed the Commune much the way we might view the ISIS takeover of Mosul.

Finally, it’s easy for me to understand how Marx and the other exiles got it wrong. I joined something like a “vanguard party formation” that turned into a toxic cult out of high school because I was convinced that the student revolts of 1968 were the harbinger of a much deeper working class radicalization in the 1970s, a radicalization that actually never happened. Instead America began to deindustrialize big time and the union movement more or less collapsed. And it remains more or less collapsed to this day.

So I don’t begrudge these earlier mistakes. I identify with them.

Comment by Hylozoic Hedgehog — December 23, 2017 @ 9:10 pm

I am impressed by your knowledge of this history. Have you written more extensively about it somewhere?

Comment by Les Evenchick — December 23, 2017 @ 9:54 pm

I will eventually write something on the 19th century “Great Game” but for Napoleon III, I became more interested in him years ago because of my interest in fascism. There was a famous 1949 book by J. Salwyn Shapiro called Liberalism and the Challenge of Fascism. He had a section where he classified Napoleon III as a “Herald of Fascism” that caused an uproar because he said Napoleon III was a kind of proto-fascist in a society not quite technologically advanced enough for totalitarian state rule.

I don’t find it a convincing argument as a whole (it’s hard to explain the 1867 “Liberal Empire” turn for example) but it is fascinating. Shapiro’s emphasis on the “left” aspect of Napoleon III’s rule strikes him as very similar to Mussolini in particular. He also quotes from Nazi books that write favorably about Napoleon III.

Shapiro’s main point was Napoleon III’s use of things like plebiscites, manhood suffrage, a controlled press, and parliament with hand-picked candidates provided a democratic facade to dictatorial rule. Also his creation of “industrial councils” for labor-capital cooperation while banning trade unions as he tried to radically industrialize France. At the same time, he used the secret police to ruthlessly suppress any left opposition at home and in the exile community in London.

After 1867, he allowed trade unions which is how the French made connections to the First International. He also legalized strikes and recognized collective bargaining. But this was an expression of just how confident he was in ruling France that he could make such concessions and woo the Left rather than out of fear of worker revolts. He believed he tamed the working class and now he could use them for his own ends.

In short, Shapiro sees Napoleon III as a kind of fuzzy avatar for 20th century fascism and not the utter dolt cartoon you get sometimes from Marx. Even if one doesn’t buy Shapiro 100%, his essay became famous for its interpretations of the Second Empire.

Anyway, that’s in part how I got interested in Napoleon III because the view Shapiro advances was so different from Marx’s dismissive treatment of Napoleon III.

In general, Napoleon III has been neglected and made almost a caricature because when we think of mid-19th century Continental Europe we think first of Bismarck. But before the Franco-Prussian War, Germany really didn’t exist. It was only in the wake of the 1866 war between Prussia and Austria that Germany began to solidify into a nation state. The Hohenzollern “Empire” really arose in the wake of the victory of the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. Before that, Napoleon III ruled the roost in Continental Europe while Germany squabbled and Austria slumbered under the Hapsburgs. But because of Napoleon III’s fall from historical consciousness, it’s easy today to read Marx and not remember just how powerful the Second Empire really was for something like two decades.

Comment by Hylozoic Hedgehog — December 24, 2017 @ 12:04 am

Thanks for the detailed explanation of the role of Napoleon!!!

Comment by Les Evenchick — December 24, 2017 @ 1:26 am

Every defense of Lenin and the Bolsheviks I’ve ever read starts with some defense of the “Red Terror”, but ignores all the anti-democratic actions of the Bolsheviks before the Civil War:

That’s why I can’t take these arguments seriously.

Comment by LetsDiscuss — December 30, 2017 @ 11:13 pm

That’s why I can’t take these arguments seriously.

—

That’s fine. Go join your local Democratic Party club and leave us alone.

Comment by louisproyect — December 31, 2017 @ 3:11 am

I support the Bolshevik leadership of the Russian revolution but never defend the “red terror” or the suppression of Kronstadt.

Comment by Les Evenchick — December 31, 2017 @ 4:15 am