(Liberated from behind New Yorker’s paywall)

The New Yorker, Nov. 15, 2019

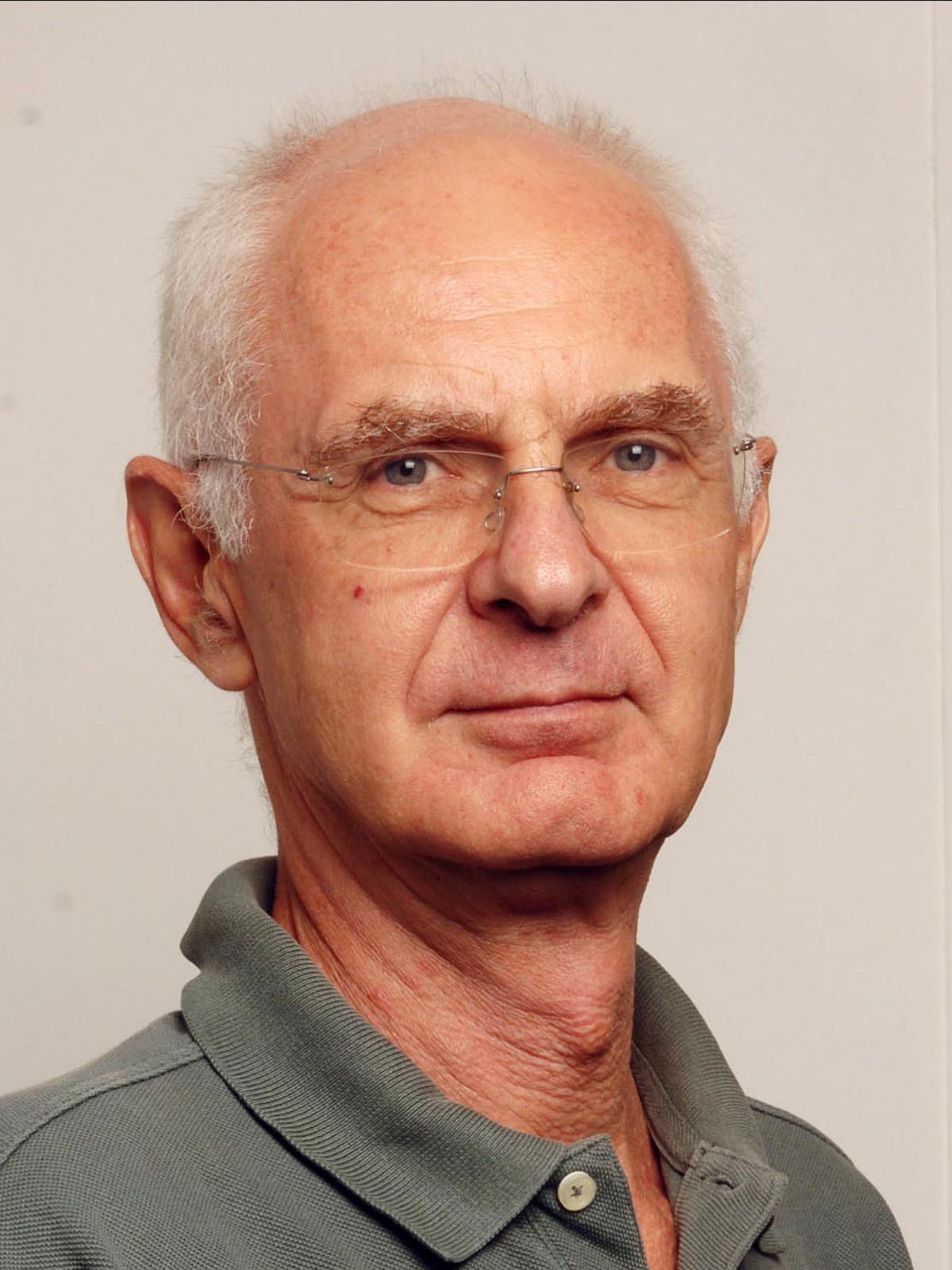

Noel Ignatiev’s Long Fight Against Whiteness

By Jay Caspian Kang

In 1995, Noel Ignatiev, a recent graduate of the doctoral program in history at Harvard, published his dissertation with Routledge, an academic press. Many such books appear then disappear, subsumed into the endless paper shuffling of the academic credentialing process. But Ignatiev was not a typical graduate student, and his book, “How the Irish Became White,” was not meant to stay within the academy. A fifty-four-year-old Marxist radical, Ignatiev had come to the academy after two decades of work in steel mills and factories. The provocative argument at the center of his book—that whiteness was not a biological fact, but rather a social construction with boundaries that shifted over time—had emerged, in large part, out of his observations of how workers from every conceivable background had interacted on the factory floor. Ignatiev wasn’t merely describing these dynamics; he wanted to change them. If whiteness could be created, it could also be destroyed.

“How the Irish Became White” quickly broke out of the academic-publishing bubble. Writing in the Washington Post, the historian Nell Irvin Painter called it “the most interesting history book of 1995.” Mumia Abu-Jamal, the activist and death-row inmate, provided an enthusiastic back-cover blurb. Today, many of the ideas Ignatiev proposed or refined—about the nature of whiteness, and about the racial dynamics that unfold among immigrant workers—are taken for granted in classrooms; they influence films, literature, and art. But Ignatiev found it hard to accept the academic rewards that came with his book’s success. Committed to radicalism, he spent much of his time in academia doing what he had done on the factory floor: publishing leaflets and zines about the possibilities of revolutionary change.

He was still at it on October 27th, when Hard Crackers, a journal that Ignatiev edited with a collection of friends and old collaborators, threw a launch party for its latest issue, at Freddy’s Bar, in Brooklyn. Wearing a white Panama hat and a loose-fitting suit, Ignatiev spoke briefly: Hard Crackers, he said, had been founded with the conviction that American society was a “time bomb,” and that its salvation could only come through the stories and actions of ordinary people. In that spirit, the journal published short, memoir-driven portraits of working Americans, in the style of Joseph Mitchell’s “Up in the Old Hotel.” This portraiture served a political purpose. Ignatiev and his fellow editors hoped to provoke small but potentially explosive moments of revelation in their readers—to create instants of autonomy which, they thought, might allow those readers to forge coalitions with other seekers of “a new society.” This philosophy, inspired by the work of the Trinidadian writer C. L. R. James, had run through all of Ignatiev’s work as a radical youth, a radical factory worker, and then, finally, a radical scholar.

Ignatiev’s speech was energetic, funny, and shot through with brio and irony. But it included a note of reflection. Ignatiev said that he had spent most of his life around people who vehemently disagreed with everything he said; he was confident that he had always been right, but also pretty sure that being right had amounted to nothing. He seemed to be posing a difficult question for those who believe, as Ignatiev did, in spontaneous revolutionary change: How do you measure success if the revolution hasn’t yet come? A few days later, Ignatiev flew out to Arizona to see his daughter and grandchildren. On November 9th, he died, at the age of seventy-eight.

The question of what Ignatiev accomplished is especially hard to answer because his radicalism took so many different forms. He was born in 1940, in Philadelphia, into a family of working-class Russian Jews. By seventeen, he had joined the Communist Party; after dropping out of the University of Pennsylvania, he moved to Chicago to work in the steel mills. He would be a factory laborer for over two decades, always with an eye toward provoking his fellow workers into looking at their struggle in new ways. In 1967, he composed a letter to the Progressive Labor Party that outlined his views. “The greatest ideological barrier to the achievement of proletarian class consciousness, solidarity and political action is now, and has been historically, white chauvinism,” Ignatiev wrote. “White chauvinism is the ideological bulwark of the practice of white supremacy, the general oppression of blacks by whites.” He argued that it would be impossible to build true solidarity among the working class without addressing the question of race, because white workers could always be placated by whatever privileges, however meaningless, management dangled in front of them. The only way to change this was for white working-class people to reject whiteness altogether. “In the struggle for socialism,” Ignatiev wrote, white workers “have more to lose than their chains; they have also to ‘lose’ their white-skin privileges, the perquisites that separate them from the rest of the working class, that act as the material base for the split in the ranks of labor.”

Many scholars have cited Ignatiev’s letter as one of the first articulations of the modern idea of “white privilege.” But Ignatiev’s version differs from the one we often use today. In his conception, white privilege wasn’t an accounting tool used to compile inequalities; it was a shunt hammered into the minds of the white working class to make them side with their masters instead of rising up with their black comrades. White privilege was a deceptive tactic wielded by bosses—a way of tricking exploited workers into believing that they were “white.”

In the late sixties, when Ignatiev was still working in steel mills and factories, he and a number of collaborators started the Sojourner Truth Organization, which aimed to approach labor organizing through the lens of race. S.T.O. members entered factories with two main goals: collaborating with black and Latino worker organizations, and putting Ignatiev’s theory of white-skin privileges into action. The white workers, Ignatiev believed, were capable of repudiating their whiteness; they needed only to be provoked into consciousness. The S.T.O. hoped to accomplish this through the dissemination of workplace publications, such as the Calumet Insurgent Worker, and constant conversation. In an essay titled “Black Worker, White Worker,” from 1972, Ignatiev examined what he called the “civil war” in the minds of his white colleagues in plants and steel mills. It begins with an anecdote:

In one department of a giant steel mill in northwest Indiana a foreman assigned a white worker to the job of operating a crane. The Black workers in the department felt that on the basis of seniority and job experience, one of them should have been given the job, which represented a promotion from the labor gang. They spent a few hours in the morning talking among themselves and agreed that they had a legitimate beef. Then they went and talked to the white workers in the department and got their support. After lunch the other crane operators mounted their cranes and proceeded to block in the crane of the newly promoted worker—one crane on each side of his—and run at the slowest possible speed, thus stopping work in the department. By the end of the day the foreman had gotten the message. He took the white worker off the crane and replaced him with a Black worker, and the cranes began to move again.

A few weeks after the slowdown, several of the white workers who had joined the black operators in protest took part in meetings in Glen Park, a virtually all-white section of Gary, with the aim of seceding from the city, in order to escape from the administration of the black mayor, Richard Hatcher. While the secessionists demanded, in their words, “the power to make the decisions which affect their lives,” it was clear that the effort was racially inspired.

To Ignatiev, these contradictions revealed a white mind perpetually battling with itself. On one side were the learned behaviors, expectations, and falsehoods associated with being “white”; on the other was the recognition, however suppressed and forbidden, that black and white workers’ concerns were aligned. The learned behaviors triumphed, Ignatiev thought, because of “the ideology and institution of white supremacy, which provides the illusion of common interests between the exploited white masses and the white ruling class.” In the workplace, Ignatiev had seen white people who seemed to be enforcing their whiteness only out of habit, or because they feared social rebuke, or suffered under the illusion that they might one day ascend to the ownership class. Their “civil war,” he thought, was winnable: one just had to show the white workers that their true enemies were the bosses.

Around that time, according to Ignatiev’s longtime friend and collaborator Kingsley Clarke, the steel industry had placed racist restrictions on black and Latino laborers, who were given dangerous jobs in blast furnaces and ovens and blocked from moving into safer and higher-paying positions within plants. The federal government eventually intervened, through an early iteration of the Affirmative Action program, and Ignatiev and the S.T.O. created smaller organizations that aimed to force the larger trade union to comply with the new law. Ignatiev found that many black workers were receptive to those efforts; he felt that he never quite broke through with whites. “The only white people who seemed to sympathize were the evangelical Christian types,” Clarke told me. “But when it came to asking them to open up the jobs for the black workers, none of them wanted to do that.” Ignatiev was discouraged; at the same time, Clarke never saw him waver in his beliefs. “Noel kept saying, look, if we can just change five people’s minds, we can change the world!”

In the eighties, the economy began to shift. Automation took root, and plants began laying off workers. Contemplating the large, industrial workforces of prior decades, Ignatiev had been able to imagine workers forming councils, seizing the means of production, and deposing their bosses. But, as factories emptied out, he no longer knew where to look. In his forties, he, too, was laid off. He decided to go back to school. A friend from S.T.O., who had gotten into Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, persuaded the administration to admit Ignatiev, despite the fact that he lacked a bachelor’s degree. Ignatiev enrolled, then transferred to the history department, where he worked toward his doctorate.

Ignatiev was now a student at the most prestigious university in the world. But he still believed in creating literary projects unencumbered by the traditional press and its credentialled demands. In 1993, he and his friend John Garvey, a former New York City cab driver whom he’d met on the radical labor circuit, started Race Traitor, a journal with the motto “Treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity.” John Brown, the white man who led a small militia of black men as they raided an arsenal, at Harpers Ferry, in hopes of sparking an armed slave rebellion, became their lodestar—an example of what it might look like to reject one’s whiteness. Ignatiev and Garvey, who is also an editor at Hard Crackers, called for an “abolition of the white race.” This prompted the expected outrage from right-wingers, who heard a call for extinction, but also upset liberals, who saw them as impractical troublemakers.

In 1995, Ignatiev finished the dissertation that would become “How the Irish Became White.” Not long ago, someone asked him why he had written the book. “The country is divided into masters and slaves,” Ignatiev wrote:

A big political problem is that many of the slaves think they are masters, or at least side with the masters at crucial moments—because they think they are white. I wanted to understand why the Irish, coming from conditions about as bad as could be imagined and thrown into low positions when they arrived, came to side with the oppressor rather than with the oppressed. Imagine how history might have been different had the Irish, the unskilled labor force of the north, and the slaves, the unskilled labor force of the South, been unified. I hoped that understanding why that didn’t happen in the past might open up new possibilities next time.

The book was a hit, by academic standards. Ignatiev now had a powerful platform. But he was also a decade removed from the steel mills, and he was unsure how much a book could really do. Privately, he questioned the value of his new life in the highest reaches of the academy. His on-campus provocations—which included a 1992 incident in which he called for the removal of a Kosher toaster oven in a student dormitory—only caused bewilderment amongst students and administrators.

By 1998, it was time for him to move on. He accepted a post at Bowdoin College, a small school in Maine that mostly catered to white New England prep schoolers. The first class he taught there was a freshman seminar on the making of race; his most adoring student that semester was me, a naïve, vain eighteen-year-old Korean immigrant from North Carolina who desperately wanted to live outside the confines dictated by his race and his own privilege. Ignatiev, with his stories of working in the steel mills, his scorn for credentialled people, and his unwavering belief that a society free from white supremacy was possible, provided a model of a life worth living. I attended all of his office hours, learned to idolize John Brown, and read everything he put in front of me. In my dorm room and in the cafeteria, I talked excitedly to my confused friends about revolutionary politics and abolishing whiteness. At the end of that year, I dropped out and enrolled in Americorps, in hopes of becoming a radical.

I learned, ultimately, that I didn’t have the strength of his convictions. I could never see a new society in my co-workers or, perhaps more importantly, in myself. Even so, I kept looking for traces of what Ignatiev was talking about. There are moments—observing a seemingly small gesture of kindness between two protesters in St. Paul, or noticing the elegant design of the food halls at Standing Rock—when some great possibility seems to reveal itself. When that happens, I think immediately of Ignatiev and his belief in the revolutionary potential of ordinary Americans.

A couple of months before he died, I drove up to see Ignatiev at his home in Connecticut. His illness prevented him from swallowing, but he wanted to cook dinner for me in his back yard, where he had fitted a large wok over a rusty propane ring. “Even though I can’t eat anymore, I still find it relaxing to cook,” he told me. As we chopped up the vegetables in a light rain, we talked about all the things we had discussed in his office—John Brown, labor movements, the need to break away from credentialled society. Just as he would a few weeks later, at Freddy’s Bar, he expressed doubt about whether his work had amounted to anything.

I am not so vain as to believe that Noel’s influence on my life provides proof that his work, in fact, made a difference. If his ideas about whiteness and of “white privilege” became fashionable within the academy, they later took on forms he could barely recognize, and oftentimes, despised. He was bewildered by the rise of a style of identity politics that reified the fictions of race and, through its fixation on diversity in élite spaces, abandoned the working class. And as a lifelong radical he took little solace in the rise of a young, insurgent left drawn to the reformist revolution of Democratic Socialism. These movements, I imagine, must have felt like defeats to Ignatiev. We are very far from the abolition of the white race, and there are very few people who believe that changing the minds of five, much less five hundred thousand people, could potentially revolutionize the world.

And yet, from another perspective, there is no political or literary trend—or President—capable of derailing Ignatiev’s true lifelong project. In his writing, and in Race Traitor and Hard Crackers, Ignatiev demonstrated the transformative power of working-class stories. His radicalism was always tethered to specific people, who, in their own ways, inspired sympathy and a desire for connection. That specificity will always be relevant; it may be especially so at a moment of cynical alienation, when identities have become recitations rather than communities. There is enduring power in the narratives he collected and shared—the stories of people he met as a child, in Philadelphia, or in the plants and mills of Chicago, or in his classrooms. My favorite of these stories is included in the introduction to “How the Irish Became White”:

On one occasion, many years ago, I was sitting on my front step when my neighbor came out of the house next door carrying her small child, whom she placed in her automobile. She turned away from him for a moment, and as she started to close the car door, I saw that the child had put his hand where it would be crushed when the door was closed. I shouted to the woman to stop. She halted in mid-motion, and when she realized what she had almost done, an amazing thing happened: she began laughing, then broke into tears and began hitting the child. It was the most intense and dramatic display of conflicting emotions I have ever beheld. My attitude toward the subjects of this study accommodates stresses similar to those I witnessed in that mother.

Sometimes, while walking around gentrifying Brooklyn, I will see young, white progressives talking to the people whom they are displacing. There’s an officiousness—an almost disingenuous toadying—to these interactions that I, with my modern, fashionable prejudices, find a bit funny and gross. Do they believe that the contradictions between their stated politics and their actual lives can be cleansed through ritualistic bonhomie? Or are they just saying an extended goodbye to their temporary neighbors? Ignatiev might have looked at those same conversations and seen people who desperately wanted to be saved from their whiteness. He might have walked by, with a generosity of spirit that I do not possess, and dropped a few leaflets at their feet, filled with enthusiastic, optimistic provocations, and unreasonable demands.