Generally, I try to read as little as possible about a film before I watch a screener in order to avoid the possibility that I might be influenced by other critics. All I knew about “Nomadland” is that it starred Frances McDormand as a sixtyish woman, who after losing everything in the 2008 financial crisis, becomes a “nomad”. This means that she travels around the country in a van taking menial jobs like in an Amazon warehouse or scrubbing toilets. With this in mind, I wondered if I was about to see a “Grapes of Wrath” updated for our epoch.

The film begins with a Steinbeckian touch. We see Fern (McDormand) loading her van with her belongings after the only employer in Empire, Nevada—a sheetrock factory—has closed for good. Like the Joads in “Grapes of Wrath” being foreclosed, she is forced by economic circumstances to look for salvation elsewhere. Like the Joads with their loaded jalopy, her road to a better life is filled with potholes. Her first job is working in an Amazon warehouse, where we expect her to end up either injured or too exhausted to keep up with the pace. To my surprise, she and other elderly women lugging cartons onto conveyor belts appear to be holding their own. After work, she retires to her van, eats a rudimentary meal, and prepares for the next day. So, I wondered when was the clash with the capitalist class going to begin.

It turns out that the film had less in common with “Grapes of Wrath” than it does with road movies like “Easy Rider” or “Five Easy Pieces”. The nomads in “Nomadland” are men and women who travel around the country in RVs or vans rather than motorcycles but with the same sense of wanderlust. Since many of you are probably not familiar with “Five Easy Pieces,” this stars Jack Nicholson (who was also in “Easy Rider” as a companion to the two motorcycle road warriors) as a man working on oil rigs in the southwest, who lives in cheap motels, and hangs out in tawdry roadhouses just like other roughnecks. It turns out, however, that this is just an appearance. In reality, Nicholson is from a wealthy family and a trained classical pianist running away from his past.

Shortly, I will explain how this connects with McDormand’s character but first I will point out that director Chloé Zhao never had the slightest interest in agitprop. In a note attached to my DVD screener, she revealed her intentions:

Having grown up in big cities in China and England, I’ve always been deeply drawn to the open road — an idea I find to be quintessentially American — the endless search for what’s beyond the horizon. It’s filled with stories of hardship, perseverance and co-existence — people helping each other, working together to survive when they disagree on almost everything. It was the spirit of the Old West and it’s still the spirit of the road today.

The open road? That’s what Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper’s characters sought in “Easy Rider”. Instead of horses, they rode Harleys. Likewise, the elderly men and women wandering around the country for dead-end jobs have their own steeds: vans, trailers, and RV’s. In “Easy Rider”, the two heroes stop at a hippie commune to enjoy drugs and sex. As for Zhao’s nomads, including Fern, they end up at a rent-free trailer park where communal meals are shared. No drugs, no sex, but the old folks get by drinking beer and making small talk.

As for the comparison with “Five Easy Pieces”, we learn (spoiler alert) that Fern has a wealthy sister who has invited her numerous times to come live with her. But Fern prefers to live in a tiny van without running water and heat. The closest the film comes to depicting the miseries of being homeless (the nomads like to describe themselves as houseless), we see Fern with an onset of diarrhea that she relieves by crapping into a bucket in her van.

The film is based on a nonfiction work of the same name written by Jessica Bruder in 2017. I have no idea whether Bruder downplayed the miseries of the people she interviewed, but a NY Times review by Arlie Russell Hochschild cannot help but question the lack of a class perspective. Hochschild is the author of a book titled “Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right” that tried to get to the bottom of why people in Louisiana voted for rightwing politicians despite being screwed by them through low-paying jobs and exposure to toxic chemicals. Like Bruder, she lived among the people she interviewed and tried to bond with them. This was her perceptive take on something that was missing in the book and, more egregiously so, in the film (the Linda mentioned in the excerpt is a character a lot like Fern):

What forces set these nomads in motion? Here I wish Bruder had given us a view from beyond the driver’s seat. For years, stockholders have taken the lion’s share of rising corporate profits, leaving a shrinking share to the middle- and working-class worker. The current administration and Congress aim to cut the nation’s safety net and to loosen regulations on banks, stirring fears of another devastating crash. The stage seems set to leave Americans on their own to travel a potentially bumpy economic road, a scene that would seem to fly in the face of the picket-fence stability and localism bandied about in conservative rhetoric. Republicans like to talk about “freedom,” but the tax reform they’re currently proposing would most likely widen the gap between rich and poor even further, reducing Linda’s freedom to stay put if she wanted to.

As for our own nomads, I recommend Marxmailer Michael Yates’s “Cheap Motels and a Hot Plate: An Economist’s Travelogue”. After retiring from decades of teaching economics, Michael and his wife Karen became nomads for many of the same reasons as the film’s subjects. They enjoyed being footloose and were open to taking low-paying jobs that were often the only kind available in the rugged back country they hoped to see in their peregrinations. Also, they always stayed indoors even if it was in a cheap motel! At Michael’s blog, titled the same as his book, you can read a chapter. From what I’ve read in this book, it would have made for a much more interesting film:

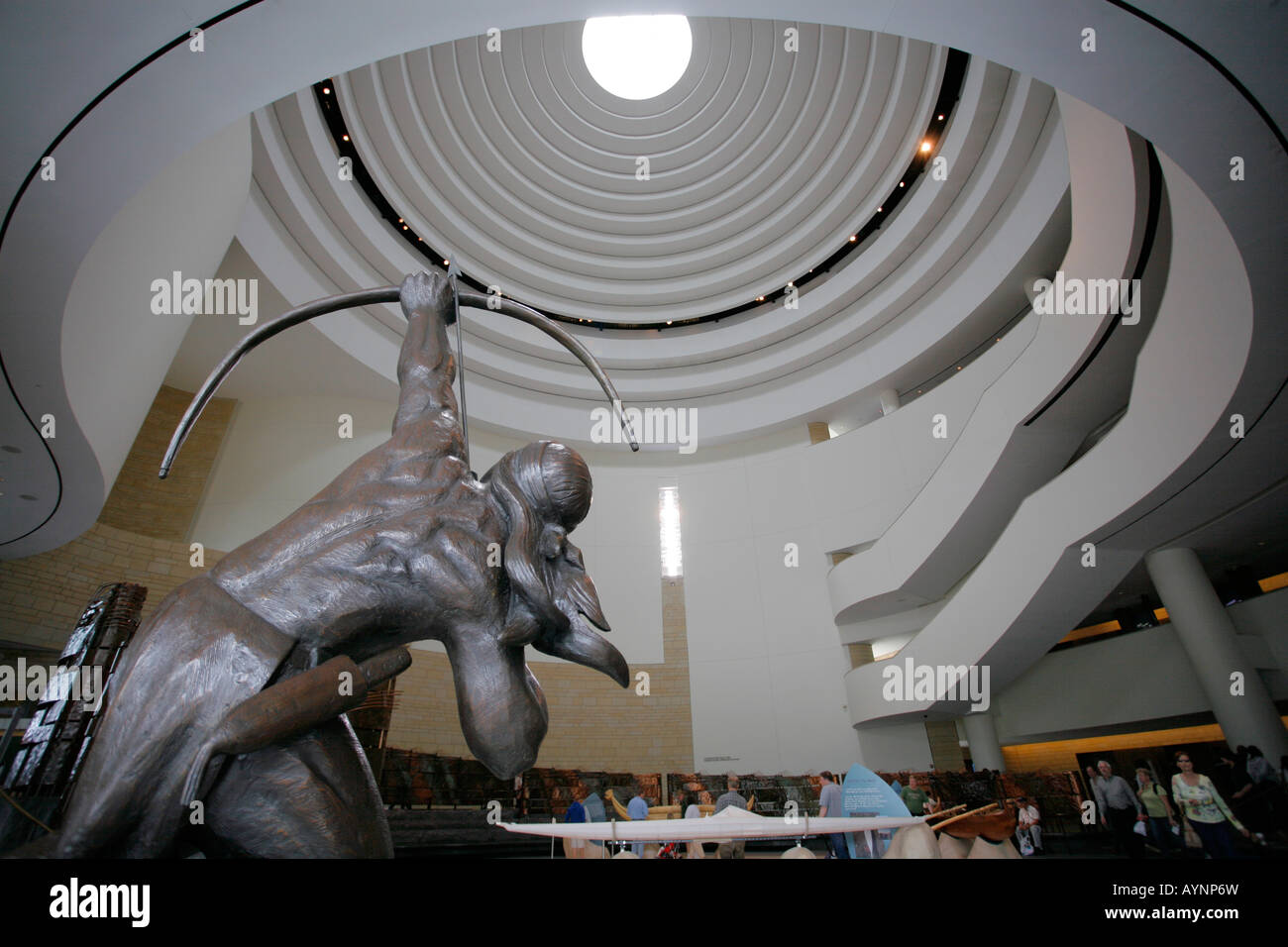

Again in Flagstaff, we were enjoying the exhibits in the Museum of Northern Arizona. We ended our visit with a stop at the museum’s bookstore. We were admiring the Indian-made works of art for sale when an Indian artist came in and showed the manager some of his jewelry and asked if the museum was interested in buying his pieces. Apparently the craftsmanship was good, but the Indian had been drinking and was known to the manager. The manager and his assistant treated this man as if he were a pathetic drunk unworthy of their time. He kept lowering his price, giving up whatever pride he had to these white people with money. A few minutes later, he was dismissed. After he left, the two museum staffers mocked him. The assistant, not realizing her ignorance, said that perhaps it was time for the Indian to join AA. We left the museum with heavy hearts. It was as if the history of white oppression of Indians had been reenacted in microcosm before our eyes.

In Estes Park, people smugly said about a group of shabby riverside shacks not far from our cabin, “Oh, that’s where the Mexicans live.” The local peace group didn’t bother to solicit support from local Mexicans because “They probably wouldn’t be interested. They have to work too hard and wouldn’t have time.” We were talking to a jewelry store owner who, after remarking on how much safer (often a code word for “whiter”) Estes Park was than his former home in Memphis, Tennessee, said that the Estes Park crime report was pretty small and those arrested always had names you couldn’t pronounce. (Those damned Mexicans again.) In the laundromat we met a woman from the Bayview section of Brooklyn, and she said that she had moved here because you couldn’t recognize her Brooklyn neighborhood anymore. She told us, without I think realizing how racist she sounded, that there were so many Arabs there now that locals call it “Bay Root.” “Get it?,” she said, “Bay Root.”